In SQL Server, every connection to the database engine is assigned a Session Process ID, commonly known as a SPID.

There are situations where you may need to kill a SPID in SQL Server. This typically occurs when a session is blocking other queries, running indefinitely, holding locks during maintenance, or preventing a database from being restored or dropped.

Two weeks ago I was on call on a Saturday evening when an alert came in. An important database was growing rapidly, tempdb was increasing and nearing capacity, and a service interruption was about to happen. A developer had executed an ad hoc SSMS query on the Friday and walked away for the weekend. Killing that session was the only realistic option.

Killing a SPID is a valid DBA action, but it must be done deliberately and with a clear understanding of the consequences.

This guide walks through how to identify the correct SPID, terminate it safely, and understand what really happens when you do.

What is a SPID in SQL Server

A SPID uniquely identifies a session connected to SQL Server. Every user connection, background task, and internal process runs under a session ID.

You can view active SPIDs using:

- Activity Monitor in SSMS

- sp_who2

- sp_whoisactive

- Dynamic Management Views

System processes often occupy lower session IDs, while user sessions typically appear above 50. This is not a strict rule, but it is commonly observed.

When Should You Kill a SPID

The KILL command should not be routine. It is a corrective action.

Common scenarios include:

- A blocking session disrupting an application

- A long running query that is clearly stuck

- A database that cannot be dropped due to active connections

- A runaway process consuming excessive CPU, memory, or I/O

If you are investigating blocking specifically, refer to my other post: How to Check Blocking in SQL Server.

Whenever possible, address the root cause. Optimising the query, improving indexing, or correcting transaction scope is preferable to terminating sessions reactively.

How to Identify the Correct SPID

Before terminating anything, confirm you are targeting the correct session.

The following query shows active user sessions and key runtime metrics:

SELECT

s.session_id,

s.login_name,

s.host_name,

s.program_name,

r.status,

r.blocking_session_id,

r.cpu_time,

r.total_elapsed_time / 1000 AS elapsed_seconds,

r.wait_type,

r.wait_time,

r.open_transaction_count

FROM sys.dm_exec_sessions s

JOIN sys.dm_exec_requests r

ON s.session_id = r.session_id

WHERE s.is_user_process = 1

ORDER BY r.cpu_time DESC;When reviewing results, focus on:

- Non zero blocking_session_id

- Long elapsed time

- High wait times

- Open transactions

Always confirm you are targeting the lead blocker. Killing a session that is itself blocked will not resolve the chain.

How to Kill a SPID in SQL Server

KILL is simple to execute, but its behaviour under load or during large rollbacks is not always simple. Before using it in production, review the official Microsoft KILL documentation, especially if you are dealing with anything beyond a straightforward session termination.

Once you are confident the session is safe to terminate, use the KILL command.

KILL <SPID>;Example:

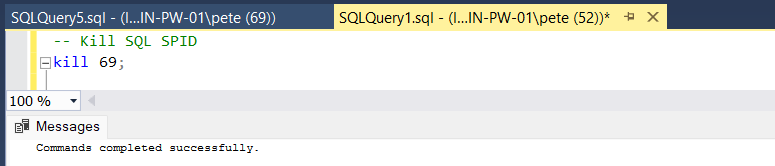

KILL 69;

The KILL statement ends the user session associated with that session ID. Internally, SQL Server stops the connection and begins rolling back any active transactions tied to it.

If there is significant work to undo, the KILL statement itself can take time to complete. Large transactions do not disappear instantly and must be fully reversed before SQL Server can release the associated locks.

You cannot cancel the rollback once it has started.

KILL can also be used with a Unit of Work (UOW) identifier when dealing with orphaned or in doubt distributed transactions involving MS DTC, although this is far less common in typical SQL Server DBA work.

Monitoring Rollback Progress

If the killed session had an open transaction, SQL Server must roll it back. The rollback phase can take longer than the original transaction, particularly if large data modifications were involved.

To check rollback status:

KILL <SPID> WITH STATUSONLY;Example:

KILL 69 WITH STATUSONLY;This may return:

- Percentage complete

- Estimated time remaining

In some cases it returns no output. That is normal behaviour.

Rollback itself can continue holding locks. In high volume systems, this may temporarily increase blocking before the system stabilises.

Rollback duration is directly tied to the amount of work that must be undone. Large transactions can take a very long time to reverse. There is an old SQL podcast episode that shares a horror story about a rollback that ran for two months after a SPID was killed. Extreme, but technically possible.

Once rollback begins, there is no way to cancel it, so think carefully before issuing KILL against a session with a large open transaction.

Killing All User Sessions on a Database

Sometimes you need everyone out of a database, usually when you are restoring it, dropping it, or doing maintenance that requires exclusive access and SQL Server is refusing because active connections still exist.

If that is the situation you are dealing with, I have covered it properly in a separate guide: How to Kill All User Sessions on a Database in SQL Server. That post walks through when it actually makes sense to do this and how to handle it safely without causing unnecessary disruption.

Sessions You Should Never Kill

System sessions should not be terminated.

Microsoft’s documentation for the KILL command makes this clear. You cannot kill your own session, and certain internal SQL Server processes must never be terminated.

These include:

- AWAITING COMMAND

- CHECKPOINT SLEEP

- LAZY WRITER

- LOCK MONITOR

- SIGNAL HANDLER

These are core engine processes. SQL Server will usually prevent you from killing them, but it is important to understand what they are before attempting to terminate any low numbered SPIDs.

You can confirm your current session using:

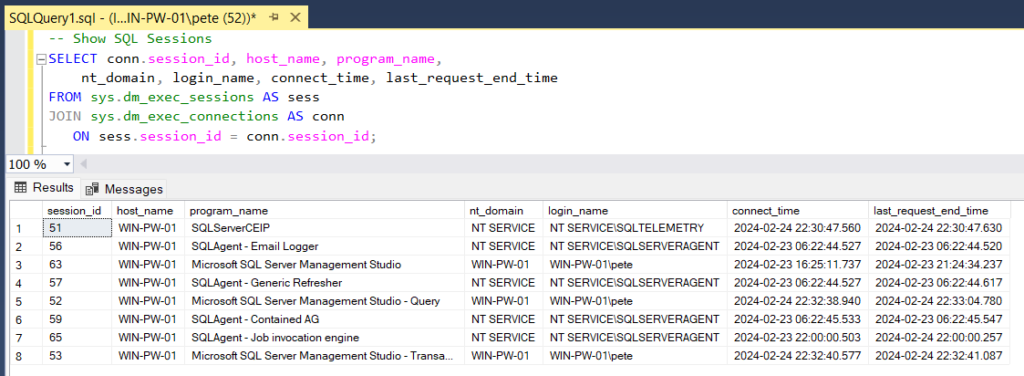

SELECT @@SPID;To review active sessions more broadly, query:

- sys.dm_exec_sessions

- sys.dm_exec_requests

- sys.dm_tran_locks

If a session is in rollback after being killed, sp_who will show the status as KILLED/ROLLBACK.

For a full breakdown of the behaviour and limitations of the KILL command, including distributed transactions and edge cases, see the official Microsoft documentation for KILL (Transact SQL).

Production considerations

Before executing KILL:

- Confirm the session is the lead blocker

- Review open_transaction_count

- Assess impact to users

- Understand potential rollback duration

Large transactions can take significant time to reverse. Once rollback begins, it cannot be stopped.

If you frequently need to kill SPIDs in SQL Server, investigate:

- Query design

- Indexing strategy

- Transaction scope

- Application behaviour

KILL is a control mechanism. It is not a performance tuning strategy.

Leave a Reply